I N T R O D U C T I O N

Tucked down a quiet side street in Woodbrook, in western port of Spain, Trinidad, stands the only memorial to the woman who single-handedly rescued and revived West Indian folk dance from ignominy and oblivion. a small, angular white building, it opens directly onto the pavement of Roberts Street, a narrow cross-street usually crammed with parked cars. number 95 occupies a lot intended for a small family home, which is exactly what it housed until Beryl McBurnie made other plans for it almost a century ago: one day, she decided, this would be the site of the Little Carib Theatre.

In the opening-night programme of the theatre in 1948, future prime minister Dr Eric Williams wrote: “it is people like Beryl McBurnie who will improve conditions in the West indies and upon whom more than anything else the future of the West indies will depend.” Today, a lifetime later, all that many people know of her is that she founded the Little Carib Theatre – but not the significance of the building or what happened there.

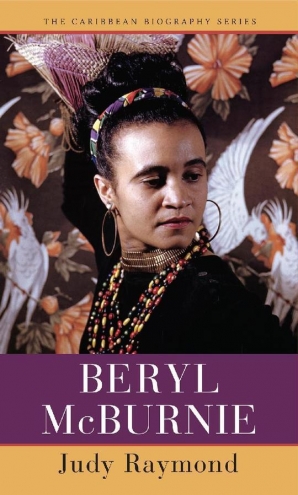

McBurnie herself was modest about what she personally had accomplished, but she knew the work was important. “I’m very interested in the classics; nothing can be more beautiful than Tristan und Isolde, nothing. but,” she went on passionately, “you can’t give a little girl an aria from the Meistersingers to sing in a competition for her country when there’s a gallery of folk songs or even calypso, can you?” (Judy Raymond, “Lady of the big idea”, Sunday Express, 17 October 1993, sect. 2, 1). She explained her life’s work in another interview, in her sixties, dressed – costumed – in one of her usual eye-catching outfits: a white full-length flounced dress with lace at the wrists, topped with a colourful headwrap and overskirt (a version of the Martiniquan-style douillette worn to dance the belé). in her cut-glass diction, she recalled what had motivated her to return to the Caribbean after several years of studying and performing successfully in the United States. She described her own early, colonial education in dance: “We would be dancing nothing Trinidadian, nothing West Indian. The coloured child in dance or theatre was never really thought about, and something had to be done. What happened with me – it emerged, really; i didn’t set out to make a political question of it; it just happened naturally.”1

McBurnie was visionary, charismatic, charming, knowledgeable, driven, persistent and inspiring, but she did not achieve everything she set out to do, though today’s Little Carib Theatre is grand compared with the original. her determination led McBurnie to build it in the face of major obstacles, among them lack of funds and frequent threats of demolition. That same stubbornness kept her from allowing the theatre to evolve beyond her own personal vision –although a company had been set up to run the theatre, and she was just one of several people who had a say in it. The theatre companies that used to share the space have moved on, including the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, founded here by Nobel laureate Derek Walcott in the late 1950s. as for the Little Carib Dance Company, it ceased to exist long before her death.

In October 2016, McBurnie’s second attempt to further her life’s work, the Folk house, literally crumbled into dust, demolished at the behest of its new owners (“home of Little Carib Founder Demolished”, Sunday Guardian, 18 September 2016). The building, a few blocks west of the theatre, was her own home, but she had tried to make it into a training centre for the arts.2

Just as the Folk house is gone, so are the dances McBurnie created. As Rex Nettleford wrote, “Dance is among the most ephemeral of the arts, and dance companies are fragile plants that require patient and sensitive nurturing to survive.”3

But McBurnie’s work was not in vain. it continues through the many theatre companies, actors, dancers, musicians, folk-dance groups, and other visual and literary artists who discovered and honed their talents at the Little Carib. Her influence was felt across the region and beyond. her name still appears on the website of Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York, where she briefly studied dance education in the 1930s (www.tc.columbia.edu/danceed/). She was honoured regionally and internationally. Little Carib dancers formed their own companies locally or went on to star overseas. Locally, folk-dance traditions are now maintained not only by semi-professional, trained dance companies, but also by the community groups that perform in the prime Minister’s best Village competition every year. McBurnie lives on too through other artists who got their start at the Little Carib, whether playing steelpan, singing or designing Carnival costumes; and those in and from Trinidad and Tobago, other islands and far away who were inspired by her to start dance and theatre companies of their own.

Beryl McBurnie’s life’s work was to give West Indian people back to themselves. This book sets out to tell who she was, why she persevered in the task she set herself, and what she accomplished in her long, often seemingly thankless decades of dedication to Caribbean culture.